|

Nixon, Watergate, and the JFK

Assassination

by Mark Tracy May 13, 2000 "I suppose, really, the only two dates that most people remember where they were, were Pearl Harbor and the death of President Franklin Roosevelt." —John F. Kennedy, 7 December 1961

In fact, the plane that Nixon had taken to New York's Idlewild Airport on the day of the assassination had originated from Dallas, and Nixon had been in Dallas on the morning of the assassination. (Note: Nixon initially told the FBI that the only time he was in Dallas during 1963 was two days prior to the assassination of President Kennedy. See: Richard Nixon's Greatest Cover-Up and Nixon's Taxi-Cab Tales) While in Dallas, Nixon met with right-wing elites and executives from the Pepsi-Cola company. Dallas journalist Jim Marrs gives this account: "With Nixon in Dallas was Pepsi-Cola heiress and actress Joan Crawford. Both Nixon and Crawford made comments in the Dallas newspapers to the effect that they, unlike the President, didn't need Secret Service protection, and they intimated that the nation was upset with Kennedy's policies. It has been suggested that this taunting may have been responsible for Kennedy's critical decision not to order the Plexiglas top placed on his limousine on November 22." Notes: The Pepsi-Cola company had a sugar plantation and factory in Cuba, which the Cuban government nationalized in 1960; CIA contract agent Chauncey Holt told Newsweek magazine in 1991 that Pepsi-Cola President Donald Kendall was "considered by the CIA to be the eyes and ears of the CIA" in the Caribbean; a photograph taken on November 21, 1963 — the day before the assassination — shows Donald Kendall meeting with Richard Nixon in Dallas.* Click to view Other facts linking Nixon to the JFK assassination emerged after Nixon had become President, during the Watergate conspiracy. In his memoir, The Ends of Power, former White House Chief of Staff H. R. Haldeman cites several conversations in which President Nixon expressed concern about the Watergate affair becoming public knowledge and where this exposure might lead. Haldeman writes: "In fact, I was puzzled when he [Nixon] told me, 'Tell Ehrlichman this whole group of Cubans [Watergate burglars] is tied to the Bay of Pigs.' After a pause I said, 'The Bay of Pigs? What does that have to do with this [the Watergate burglary]?' But Nixon merely said, 'Ehrlichman will know what I mean,' and dropped the subject." Later in his book, Haldeman appears to answer his own question when he says, "It seems that in all of those Nixon references to the Bay of Pigs, he was actually referring to the Kennedy assassination." If Haldeman's interpretation is correct, then Nixon's instructions for him to, "Tell Ehrlichman this whole group of [anti-Castro] Cubans is tied to the Bay of Pigs," was Nixon's way of telling him to inform Ehrlichman that the Watergate burglars were tied to Kennedy's murder. (It should be noted that many Cuban exiles blamed Kennedy for the failure to overthrow Castro at the Bay of Pigs, pointing to Kennedy's refusal to allow the U.S. military to launch a full-scale invasion of the island.) Haldeman also links the Central Intelligence Agency to the Watergate burglars and, by implication, to the Kennedy assassination. Haldeman writes, "...at least one of the burglars, [Eugenio] Martinez, was still on the CIA payroll on June 17, 1972 — and almost certainly was reporting to his CIA case officer about the proposed break-in even before it happened [his italics]." The other Watergate conspirators included ex-FBI agent G. Gordon Liddy, ex-CIA agent James McCord, ex-CIA agent E. Howard Hunt, and Bay of Pigs veterans Bernard Barker, Frank Sturgis and Virgilio Gonzales. E. Howard Hunt's relationship with the anti-Castro Cubans traces back to the early 1960s, to his days with the Central Intelligence Agency. As a CIA political officer and propaganda expert, Hunt helped plan the Bays of Pigs operation and also helped create the Cuban Revolutionary Council — a militant anti-Castro organization. Hunt would later retire from the CIA (at least ostensibly) to become covert operations chief for the Nixon White House. (Note: Hunt maintained a working relationship with the Central Intelligence Agency even after his "retirement," obtaining camera equipment and disguises from the CIA's Technical Services Division for use in the Watergate burglary.) Several reports over the years have placed Hunt in Dallas at the time of the Kennedy assassination. In 1974, the Rockefeller Commission concluded that Hunt used eleven hours of sick leave from the CIA in the two-week period preceding the assassination. Later, eyewitness Marita Lorenz testified under oath that she saw Hunt pay off an assassination team in Dallas the night before Kennedy's murder. (Hunt v. Liberty Lobby; U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida; 1985) Click to read transcript In taped conversations with Haldeman, Nixon is obviously worried about what would happen if Hunt's involvement in the Watergate conspiracy came to light. Nixon says, "Of course, this Hunt, that will uncover a lot of things. You open that scab, there's a hell of a lot of things, and we feel that it would be very detrimental to have this thing go any further ... the President's belief is that this is going to open the whole Bay of Pigs thing up again." Click to Listen: President Nixon instructs Haldeman on what to tell the CIA (text below) NIXON: When you get in to see these people, say: "Look, the problem is that this will open the whole, the whole Bay of Pigs thing, and the President just feels that..." ah, I mean, without going into the details of, of lying to them to the extent to say that there is no involvement. But, you can say, "This is sort of a comedy of errors, bizarre," without getting into it, "The President's belief is that this is going to open the whole Bay of Pigs thing up again. And, ah because ah these people are playing for, for keeps and that they should call the FBI in and we feel that ... that we wish for the country, don't go any further into this case, period!"

Eleven days after Hunt's arrest for the Watergate burglary, L. Patrick Gray, acting FBI Director, was called to the White House and told by Nixon aide John Ehrlichman to "deep six" written files taken from Hunt's personal safe. The FBI Director was told that the files were "political dynamite and clearly should not see the light of day." Gray responded by taking the material home and burning it in his fireplace. John Dean, council to the president, acted similarly by shredding Hunt's operational diary.

Furthermore, as former White House correspondent Don Fulsom reveals, "The newest Nixon tapes are studded with deletions — segments deemed by government censors as too sensitive for public scrutiny. 'National Security' is cited. Not surprisingly, such deletions often occur during discussions involving the Bay of Pigs, E. Howard Hunt, and John F. Kennedy. One of the most tantalizing nuggets about Nixon's possible inside knowledge of JFK assassination secrets was buried on a White House tape until 2002. On the tape, recorded in May of 1972, the president confided to two top aides that the Warren Commission pulled off 'the greatest hoax that has ever been perpetuated.' Unfortunately, he did not elaborate." References: DiEugenio, James. Destiny Betrayed: JFK, Cuba, and the Garrison Case. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012. Douglass, James. JFK and the Unspeakable: Why He Died and Why It Matters. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008. Fetzer, James H., editor. Assassination Science: Experts Speak Out on the Death of JFK. Chicago: Catfeet Press, 1998. Fonzi, Gaeton. The Last Investigation. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1993. Haldeman, H. R. The Ends of Power. New York: Times Books, 1978. Lane, Mark. Plausible Denial: Was the CIA Involved in the Assassination of JFK?. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1991. Marrs, Jim. Crossfire: The Plot that Killed Kennedy. New York: Carroll & Graf, 1989. Twyman, Noel. Bloody Treason: On Solving History's Greatest Murder Mystery: The Assassination of John F. Kennedy. Rancho Santa Fe: Laurel Publishing, 1997. Weissman, Steve. Big Brother and the Holding Company: The World Behind Watergate. Palo Alto: Ramparts Press, 1974.

Nixon Foundation comment: "The charge that the 37th President of the United States had any knowledge of, and indirect moral and operational responsibility in the murder of the 35th President of the United States is so reprehensible that it should render wholly illegitimate any text or narrative in which it is contained." E. Howard Hunt — CIA political officer and head of covert operations for Nixon — takes aim at Kennedy in his book, Give Us This Day: "Instead of standing firm, our government [under Kennedy] pyramided crucially wrong decisions and allowed Brigade 2506 [at the Bay of Pigs] to be destroyed. The Kennedy administration yielded Castro all the excuse he needed to gain a tighter grip on the island.... Under the administration's philosophy, the real enemy became poverty and ignorance; any talk of an international Communist conspiracy was loudly derided. Detente and a 'positive approach to easing international tensions' filled the Washington air, to the wonderment of those of us who still remembered Budapest, the Berlin Wall and the fate of Brigade 2506."

Hunt continues: "When President Kennedy on April 12 [1961] declared the United States would never invade Cuba my project colleagues and I did not take him seriously."

Author Mark Lane in his book, Plausible Denial adds: "Kennedy had said publicly that no segment of the armed forces of the United States would participate in the invasion of Cuba. At the CIA they had heard the words but wanted to believe that he meant them for public consumption only." E. Howard Hunt refused to answer whether he was in Dallas on the day that President Kennedy was murdered. Click to read this 2004 interview (Note: In a deathbed statement released in 2007, Hunt claimed first-hand knowledge of a JFK assassination conspiracy and also said that he was one of the conspirators. Hunt, however, minimized his own role in the conspiracy. He fingered his fellow officers in the CIA, David Phillips, William Harvey, and David Morales.) Regarding the Cuba situation, Theodore Sorensen, Special Counsel to John F. Kennedy, said: "We were deeply concerned that Khrushchev would respond [to a U.S. attack on Cuba] with an attack on Berlin, where he had the geographic advantage, and with nuclear weapons, which would have transformed that local battle into a terrible global struggle." After the Bay of Pigs fiasco, President Kennedy said to his friend, Assistant Navy Secretary Paul Fay: "Nobody is going to force me to do anything I don't think is in the best interest of the country. I will never compromise the principles on which this country is built, but we're not going to plunge into an irresponsible action just because a fanatical fringe in this country puts so-called national pride above national reason. Do you think I'm going to carry on my conscience the responsibility for the wanton maiming and killing of children like our children we saw here this evening? Do you think I'm going to cause a nuclear exchange — for what? Because I was forced into doing something that I didn't think was proper and right? Well, if you or anybody else thinks I am, he's crazy." Kennedy also told Paul Fay: "Now, in retrospect, I know damn well that they [the Pentagon and the CIA] didn't have any intention of giving me the straight word on this thing [the Bay of Pigs operation]. They just thought that if we got involved in the thing, that I would have to say 'Go ahead, you can throw all our forces in there, and just move into Cuba.' ... Well, from now on it's John Kennedy that makes the decisions as to whether or not we're going to do these things." "'[The Joint Chiefs] were sure I'd give in to them and send the go-ahead order to the [aircraft carrier] Essex,' he said one day to Dave Powers. 'They couldn't believe that a new President like me wouldn't panic and try to save his own face. Well, they had me figured all wrong.'" President Kennedy was correct regarding the intentions of the Joint Chiefs and the CIA. Then-CIA Director Allen Dulles lamented: "We felt that when the chips were down — when the crisis arose in reality, any action required for success [at the Bay of Pigs] would be authorized rather than permit the enterprise to fail." In a letter to Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, 1 December 1963, Kennedy's widow Jacqueline wrote: "The danger which troubled my husband was that war might be started not so much by the big men as by the little ones. While big men know the need for self-control and restraint, little men are sometimes moved more by fear and pride." "In a remarkable passage in 'One Hell of a Gamble,' a widely praised 1997 history of the Cuban missile crisis based on declassified Soviet and U.S. government documents, historians Alexksandr Fursenko and Timothy Naftali wrote that on November 29, one week after the assassination, Bobby Kennedy dispatched a close family friend named William Walton to Moscow with a remarkable message for Georgi Bolshakov, the KGB agent he had come to trust during the nerve-wracking back-channel discussions sparked by the missile crisis. According to the historians, Walton told Bolshakov that Bobby and Jacqueline Kennedy believed 'there was a large political conspiracy behind Oswald's rifle' and 'that Dallas was the ideal location for such a crime.'" "After the Bay of Pigs, Kennedy had contempt for the Joint Chiefs. I remember going into his office in the spring of 1961, where he waved some cables at me from General Lemnitzer [chairman of the Joint Chiefs], who was then in Laos on an inspection tour. And Kennedy said, 'If it hadn't been for the Bay of Pigs, I might have been impressed by this.' I think J.F.K.'s war-hero status allowed him to defy the Joint Chiefs. He dismissed them as a bunch of old men. He thought Lemnitzer was a dope." Kennedy once told Ben Bradlee, the Washington correspondent for Newsweek: "The first advice I'm going to give my successor is to

watch the generals and to avoid feeling that just because they were

military men their opinions on military matters were worth a damn." Kennedy also told Assistant Navy Secretary Paul Fay: "Looking back on that whole Cuban mess, one of the things that appalled me most was the lack of broad judgment by some of the heads of the military services. When you think of the long competitive selection process that they have to weather to end up the number one man of their particular service, it is certainly not unreasonable to expect that they would also be bright, with good broad judgment. For years I've been looking at those rows of ribbons and those four stars, and conceding a certain higher qualification not obtained in civilian life. Well, if ------- and ------- are the best the services can produce, a lot more attention is going to be given their advice in the future before any action is taken as a result of it." Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, recalling a discussion he had with Kennedy shortly after the Bay of Pigs, said: "This episode seared him. He had experienced the extreme power that these groups had, these various insidious influences of the CIA and the Pentagon on civilian policy, and I think it raised in his own mind the specter: Can Jack Kennedy, President of the United States, ever be strong enough to really rule these two powerful agencies? I think it had a profound effect ... it shook him up!" "'The Bay of Pigs fiasco broke the dike,' said one report at the time. 'President Kennedy was pilloried by the super patriots as a 'no-win' chief.... The far Right became a fount of proposals born of frustration and put forward in the name of anti-Communism.... Active-duty commanders played host to anti-Communist seminars on their bases and attended or addressed right-wing meetings elsewhere.'" "When Kennedy took office, Laos was the hot spot, and the departing President, Dwight D. Eisenhower, warned Kennedy he might have to fight there. If so, Eisenhower said, he would support the decision. Over the next few weeks Kennedy made several hawkish public statements. But after the Bay of Pigs fiasco in Cuba, he changed his attitude. He told several people, including Richard Nixon, that since 'the American people do not want to use troops to remove a Communist regime only 90 miles away, how can I ask them to use troops to remove one 9,000 miles away?'" "I don't recall anyone who was strongly against [sending ground troops into Vietnam], except one man and that was the President. The President just didn't want to be convinced that this was the right thing to do.... It was really the President's personal conviction that U.S. ground troops shouldn't go in." "'They want a force of American troops,' [President Kennedy] told me early in November. 'They say it's necessary in order to restore confidence and maintain morale. But it will be just like Berlin. The troops will march in; the bands will play; the crowds will cheer; and in four days everyone will have forgotten. Then we will be told we have to send in more troops. It's like taking a drink. The effect wears off, and you have to take another.' The war in Vietnam, he added, could be won only so long as it was their war. If it were ever converted into a white man's war, we would lose as the French had lost a decade earlier." "When Kennedy took office ... the first thing Kennedy did was to send a couple of men to Vietnam to survey the situation. They came back with the recommendation that the military assistance group be increased from 800 to 25,000. That was the start of our involvement. Kennedy, I believe, realized he'd made a mistake because 25,000 U.S. military [advisers] in a country such as South Vietnam means that the responsibility for the war flows to [the United States] and out of the hands of the South Vietnamese. So Kennedy, in the weeks prior to his death, realized that we had gone overboard and actually was in the process of withdrawing when he was killed and Johnson took over." "Iíve just been given a list of the most recent casualties in Vietnam. Weíre losing too damned many people over there. Itís time for us to get out. The Vietnamese aren't fighting for themselves. Weíre the ones who are doing the fighting. After I come back from Texas, thatís going to change. There's no reason for us to lose another man over there. Vietnam is not worth another American life." "When Malcolm Kilduff announced the death of President Kennedy at Parkland Hospital [on November 22, 1963], he was announcing also in effect the death of over 50,000 American soldiers and three million Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians from a war that would continue until 1975." "President [Kennedy] heroically kept the country out of war — against relentless pressure from hard-liners in the Pentagon, CIA and his own White House, who were determined to militarily engage the enemy in Berlin, Laos, Vietnam and especially Cuba. Kennedy knew that any such military confrontation could quickly escalate into a nuclear war with the Soviet Union. And he realized that a full-scale invasion of Cuba or Vietnam could become hopelessly bogged down, turning into a bloody and endless occupation.... The only reason Cuba didn't become the Iraq of its day was that Kennedy was too wise to be snookered by hard-liners into this trap. He had already been misled early in his administration by the CIA, which convinced him that its ragtag army of Cuban exiles could defeat Castro at the Bay of Pigs. JFK vowed that he would never again listen to these so-called national security experts...." "Arthur Schlesinger Jr., in his book 'Robert Kennedy and His Times,' documents other episodes showing President Kennedy's determination not to let Vietnam become an American war. One was when Gen. Douglas MacArthur told him it would be foolish to fight again in Asia and that the problem should be solved at the diplomatic table. Later General Taylor said that MacArthur's views made 'a hell of an impression on the President ... so that whenever he'd get this military advice from the Joint Chiefs or from me or anyone else, he'd say, 'Well, now, you gentlemen, you go back and convince General MacArthur, then I'll be convinced.'" And this from Peter Dale Scott's book, Deep Politics and the Death of JFK: "Of the more than a dozen suspicious deaths in the case of Watergate ... perhaps the most significant death was that of Dorothy Hunt [E. Howard Hunt's wife] in the crash of United Air Lines [flight 553] in December 1972. The crash was investigated for possible sabotage by both the FBI and a congressional committee, but sabotage was never proven. Nevertheless, some people assumed that Dorothy Hunt was murdered (along with the dozens of others in the plane). One of these was Howard Hunt, who dropped all further demands on the White House and agreed to plead guilty [to the Watergate burglary in January 1973]." Flight 553: Click to read Confirmation that E. Howard Hunt assumed that his wife was murdered came from his son, Saint John Hunt, who said on the Alex Jones Show (5/2/07): "Later on in [my father's] life at one of these bedside confessions ... tears started welling up in his eyes and he said, 'you know Saint I was so deeply concerned that what they did to your mother they could have done to you children' and that caused the hair on my neck to stand up — that was the first disclosure from my father that he thought there was something else going on besides sheer pilot error." Charles Colson — Nixon's special council and E. Howard Hunt's boss — was another person who thought that Dorothy Hunt was murdered. In 1974, Colson told Time magazine (7/8/74): "I think they [the CIA] killed Dorothy

Hunt."

Links:

"Apparently Nixon knew more about the genesis of the Cuban invasion that led to the Bay of Pigs than almost anyone. Recently, the man who was President of Costa Rica at the time — dealing with Nixon while the invasion was being prepared stated that Nixon was the man who originated the Cuban invasion." "We must no longer postpone making a command decision to do whatever is necessary to force the removal of the Soviet beachhead in Cuba."

*The evidence that executives of the Pepsi-Cola company, the CIA, and Richard Nixon were involved in the JFK assassination becomes even more credible when one considers that these three parties collaborated in a plot against another president: Salvador Allende, the socialist leader of Chile. As the British newspaper The Guardian reports, "...the October 1970 plot against Chile's President-elect Salvador Allende, using CIA 'sub-machine guns and ammo', was the direct result of a plea for action a month earlier by Donald Kendall, chairman of PepsiCo, in two telephone calls to the company's former lawyer, President Richard Nixon. Kendall arranged for the owner of the company's Chilean bottling operation to meet National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger on September 15. Hours later, Nixon called in his CIA chief, Richard Helms, and, according to Helms's handwritten notes, ordered the CIA to prevent Allende's inauguration."

"On evenings such as these, Deep Throat had talked about how politics had infiltrated every corner of government — a strong-arm takeover of the agencies by the Nixon White House.... He had once called it the 'switchblade mentality' — and had referred to the willingness of the President's men to fight dirty and for keeps..." "When the President does it, that means that it's not illegal." "You donít want to know." "If he gets shot, it's too damn bad." "New revelations give us both insight into the character of the thirty-seventh President of the United States, and an understanding of why Nixon spent an estimated $20 million in legal fees to try to keep the incriminating information private.... As vice president, he headed supersecret CIA/Mafia efforts to kill Cuban leader Fidel Castro, and he approved a plan to assassinate Greek shipping tycoon Aristotle Onassis ('If it turns out we have to kill the bastard,' he admonished an aide, 'just don't do it on American soil.'). As president he authorized the assassination of Chilean president Salvador Allende, and made it clear to Vietnamese president Nguyen Van Thieu, in 1972, that if he kept resisting a political settlement of the Vietnam War, he might not be around long. He concocted a plan to assassinate Panamanian strongman Omar Torrijos, and only at the last moment reportedly canceled a plan to kill columnist Jack Anderson, his nemesis in the press. It is no wonder his vice president, Spiro Agnew, feared that when Nixon asked him to resign there was an 'or else' implied. And it's no wonder star Watergate reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein feared for their lives after being warned by 'Deep Throat.'"

Nixon, Watergate, and the JFK

Assassination

|

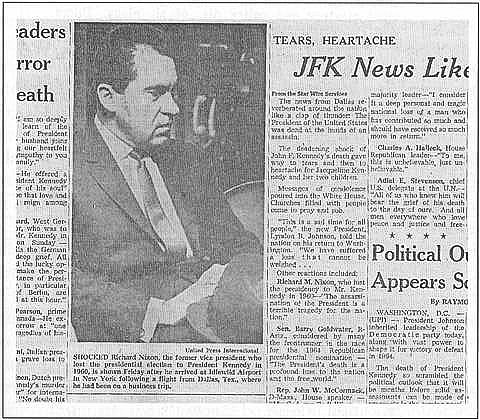

Private citizen and future president Richard Nixon claimed to

remember where he was during another momentous event — the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963. Nixon said that he first heard about Kennedy's death during a taxi ride in New York, while a press photo taken on the day of the assassination shows a "shocked Richard Nixon" at New York's Idlewild Airport.

Private citizen and future president Richard Nixon claimed to

remember where he was during another momentous event — the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas on November 22, 1963. Nixon said that he first heard about Kennedy's death during a taxi ride in New York, while a press photo taken on the day of the assassination shows a "shocked Richard Nixon" at New York's Idlewild Airport.